The History of Linen

Linen textiles can be traced back thousands of years. Learn how linen was first used, see how it's evolved over the years, and find out why it's the textile of choice for many today.

Linen in Ancient Times

Flax was the first textile produced by man—the oldest scraps of flax linen were found in prehistoric cave dwellings in the Caucasus and are estimated to be 38,000 years old!

Fast-forward to ancient Egypt in 5,000 B.C.—the Egyptians ran a moneyless economy where, instead of cash, goods were exchanged for other goods of equivalent value. As the textile used for everything from day wear to mummy bandages, flax was a fundamental part of this economy. Absorbent and heat conducting, linen was ideal for the hot Egyptian climate. Even today, flax linen used in Egyptian tombs is well-preserved, allowing us to tell the story of this ancient civilization. The use of mordants—dye-binding chemicals—had not yet reached Egypt, so the linen garments would have been in their natural color or bleached white.

The use of linen garments was echoed in other ancient Mediterranean civilizations, with Romans naming the flax plant “linum usitatissimum,” or “most useful flax.”

Two thousand years later, linen went global. The ancient Phoenicians exported linen yarn to Scotland, Persia, India, and China. In the colder regions of Europe, linen was used to make shirts, shifts, and chemises that were worn under wool outerwear. In fact, linen is the origin of the words “lining” and “lingerie.”

Mummy bandage inscribed with a falcon, ca. 1000–945 B.C., found in the tomb of Henettawy in Egypt.

Linen and Religion

The wearing of linen connotes purity in many cultures. Indeed, the ancient Egyptians believed that the gods were clothed in linen before they came to earth. The Book of Revelation—the final book of Christianity’s New Testament—states “the seven angels came out of the temple… clothed in pure and white linen.”

In “Moralia,” his first-century collection of essays, the Greek philosopher Plutarch explained why priests wore linen, rather than wool. Having shaved their hair to rid themselves of impurity, “it would be ridiculous that these persons… then should put on and wear the hair of domestic animals.” He continues: “The flax springs from the earth, which is immortal; it yields edible seeds, and supplies a plain and cleanly clothing, which does not oppress by the weight required for warmth. It is suitable for every season.”

Laminated Linen: the First Composite Material

Not only was linen the first textile, it was also involved in the production of the first known composite material—a breastplate made from layers of laminated linen worn by Alexander the Great as he conquered swathes of the Mediterranean and Asia.

However, Greek mythological hero Ajax also wore a linen composite breastplate in the Iliad, written 400 years prior, suggesting that the material had already been used for centuries.

A mosaic of Alexander the Great showing him wearing linothorax, an armor made from laminated linen.

Linen Through the Middle Ages

Linen production became a family affair in 789, when French king Charlemagne decreed that all households must cultivate flax and weave their own linen fabric. This tradition persisted well into the 18th century, with clothing, bed linen, and domestic textiles all made at home.

Over the following centuries, linen formed the foundation of many of our greatest works of art. The 11th century Bayeux tapestry, depicting William the Conqueror seizing the crown from King Harold of England, was made from 70 meters of linen. In the early 16th century, Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens inspired many European artists to switch from wood panels to linen canvas, which remains popular today.

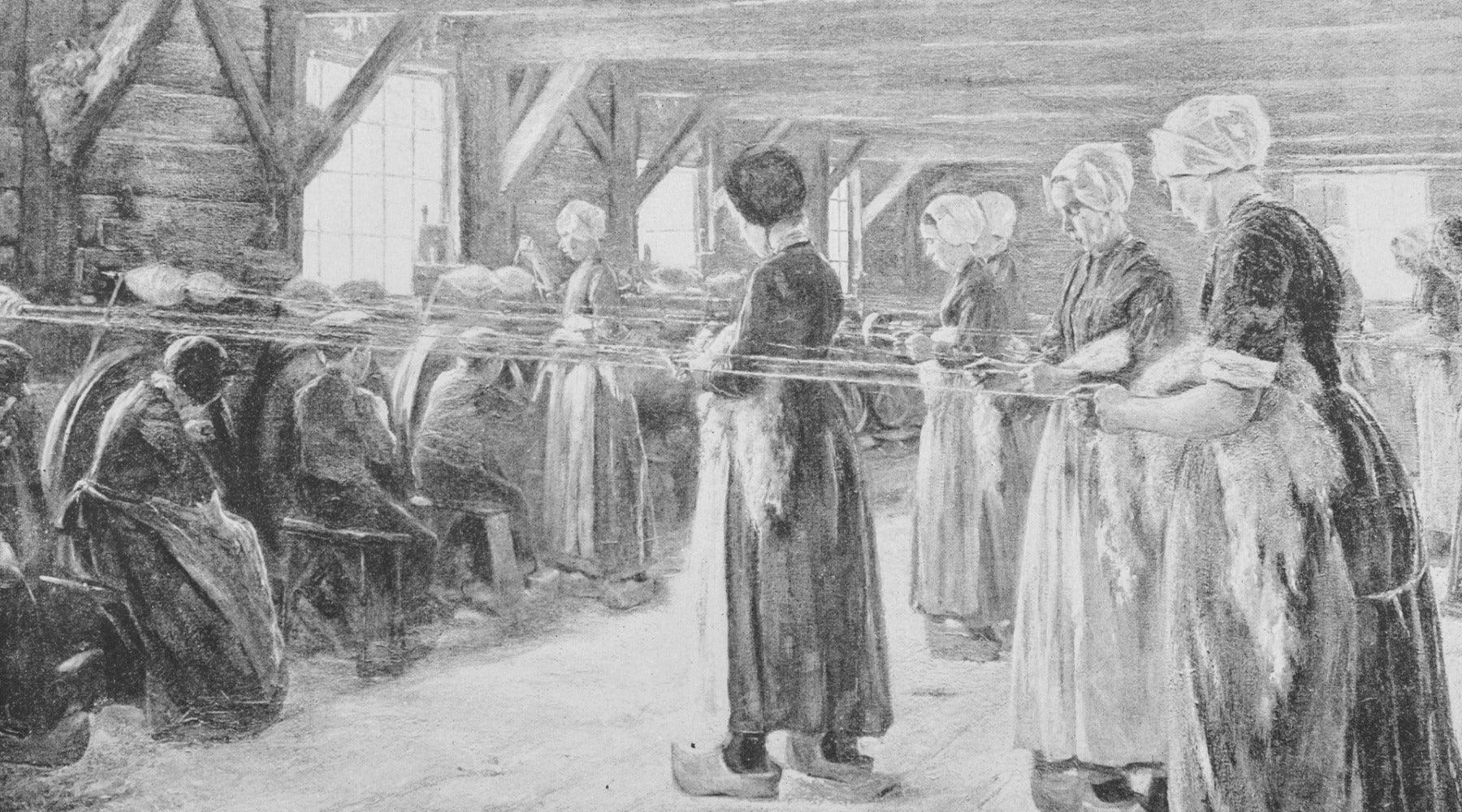

The European “Linen Belt”: the Netherlands, France, and Belgium

For the first half of the 17th century, the Dutch town of Haarlem was a major center for linen production. The town benefited from the migration of experienced linen weavers from southern Netherlands during the Dutch Revolt. Merchants from other parts of Europe also sent linen products to Haarlem for bleaching and finishing, a process immortalized in Jacob van Ruisdael’s series of paintings of Haarlem bleaching fields. The industry declined toward the end of the 17th century, as producers sought to cut costs by moving production to more rural areas.

In 16th century France, linen artisans clothed French courtiers in fine garments but much of that talent went into exile in the 17th century, when King Louis XIV outlawed Protestants from France. The artisans emigrated to Germany and northern Europe.

With the decline of the Dutch and French linen industries, a new player emerged on the map—Belgian Flanders, and the town of Tielt in particular. Although Julius Caesar had commented on the quality of Flemish linen as early as 100 B.C., it was in the 18th century that it truly came into its own. By 1840, 71% of households around Tielt were involved in linen production.

The Decline of the Linen Industry

Linen production became far easier and cheaper when Philippe de Girard developed the flax spinning machine in 1810, at the start of the Industrial Revolution. However, this was also the beginning of linen’s decline. Despite being less durable than linen, cotton was easier and cheaper to produce at scale, and so became the preferred textile for the industrial era. From the 1850s, the European linen industry went into decline.

However, linen retained niche uses, particularly during the First and Second World Wars, when it was used to make ropes, tarpaulins, and other cloth items requiring strength and durability. The German army cut off supplies of European flax, so swathes of land in Ireland and Australia were set aside for flax farming, with much of it farmed by women.

Modern Linen

The upheaval of war also caused notable linen-producing families to return to their homeland, triggering the beginning of a linen renaissance. In the 20th century, formal summerwear made from linen became popular.

Today—almost 2,000 years since Plutarch praised its purity—linen is once again the center of attention for its low environmental footprint. The rise of responsible consumerism has led many to reevaluate cheap synthetic and cotton clothing, which comes at considerable cost to the earth.

Interior trends, too, are changing to reflect more ethical consumption patterns. Gone are the inflatable plastic chairs and lava lamps of the 1990s, replaced by long-lasting wooden furniture and natural textiles such as organic flax linen. The sustainable nature of flax linen, and the fact that it’s proved itself to be a strong, durable textile for centuries, inspired us to make our European linen duvet covers. The quality of the textile has proven itself time and time again, making it the obvious textile of choice for our Danish-style bedding. We’re proud to continue to build on the history of linen with our solid color and print organic linen duvet covers.

Has anything about the history of linen surprised you? How do you use linen in your daily life? Let us know on Instagram, Pinterest, Facebook, or Twitter!

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.